Some time in early March (Phamenoth in the Egyptian calendar), around AD320, a man named Theophanes set off from the city of Hermopolis in the Nile valley on a journey to Antioch in Syria, capital of the eastern provinces of the Roman empire. Theophanes was probably a lawyer, and he was travelling to Antioch to visit the office of Dyscolius, the vicarius (deputy) to the Praetorian Prefect of the East. We don’t know the reason for his journey, but it may have been connected with a property dispute between different towns in the Hermopolis region. His round trip would take him nearly six months, but Theophanes travelled in style, staying at imperial guesthouses, bathing regularly, meeting and dining with friends and officials along the way. As a man, he is otherwise completely unknown, but his journey allows a fascinating insight into the daily life of a middle-class Roman traveller of the early 4th century AD.

We know about Theophanes today because a record of his trip, together with some letters of introduction to the officials he would meet along the way and an inventory of household possessions, was discovered in Egypt, in a cache of preserved papyri. The main document is a simple itinerary with a list of travel expenses – a dry compilation of facts, presumably compiled by his secretary. But, deciphered and studied by the historian John Matthews (in The Journey of Theophanes: Travel, Business and Daily Life in the Roman East), this basic account provides a way of reconstructing these few months in Theophanes’s life.

The document was written on the back of an official Latin petition, or subscriptio, stating the names of the reigning Caesars (junior emperors) of the day, which gives us an approximate date. Papyrus was valuable, and this would have been the equivalent of office scrap paper. The eastern empire at this point was under the rule of the Augustus Licinius, the great rival of the western emperor Constantine: fortunately, this is the exact period covered by my ‘Twilight of Empire’ novels.

Theophanes was not travelling alone, of course – wealthy Romans of his day seldom went anywhere unaccompanied. Notes in the account mention several members of his travelling retinue, most or all of them probably slaves. A man named Silvanus served as his phrontistes, or household manager, while another named Eudaimon dealt with his daily finances. There was a messenger (dromeus), appropriately called Hermes, and another named Horos. Two Egyptian slaves called Piox and Aoros seem to have acted as general helpers and baggage handlers. These, and perhaps other slaves, were collectively called paidia – ‘the boys’ – and there are frequent references to special provisions of lower-quality rations allocated to them.

Various friends and travelling companions come and go – somebody called Antoninus appears to accompany Theophanes for part of his journey. At the fortress of Babylon in Egypt (near modern Cairo) Theophanes pays for wine for ‘a Pannonian soldier’, and on the last leg of his journey, from Laodicea in Syria to Antioch, he is accompanied by ‘six Sarmatians’: these men are probably also soldiers, perhaps a military escort provided by the local governor. On that day Theophanes covered an extraordinary 64 miles, so perhaps he had joined a military group in a ride through the night to reach his final destination.

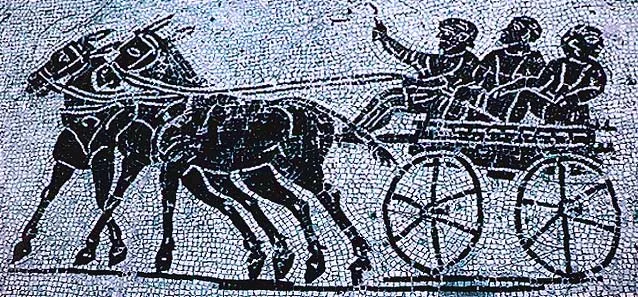

Scenes of everyday life in Antioch, from the 5th century Yakto mosaic.

Other stages of the journey were less hectic. As an important civilian travelling on official business, Theophanes could apparently make use of the imperial post-carriage service, or cursus publicus, and stay at the network of mansiones, inns or guesthouses, along the route. This allowed him to move very rapidly: he covered distances of between 16 and 45 miles daily, averaging 32 per day. Matthews estimates that he would have used two carriages and probably a wagon as well to transport himself, his staff and his travelling baggage.

The most interesting aspect of the accounts, however, are the smaller items that Theophanes pays for along the way. He makes regular visits to the baths, taking his own bath-salts (nitron) and even soap (sophonion). He eats well – daily bread of differing quality, fruit, and the typical Roman three-course meal, sometimes with the herb-flavoured white wine called absinthion, drunk as an aperitif. He frequently buys lunch or snacks for his companions too – ‘olives for lunch with Antoninus’ at one point. At Pelusium, on his journey home, the account mentions ‘snails for the boys’ – whether this was a rare treat, or all that was available, is unclear!

All of the monetary sums are given in drachmae, an obsolete Greek currency at the time but still used as a financial unit, like the Roman denarius. Theophanes’s daily transactions – or those of his slaves and treasurer – were probably carried out in nummi, the silver-washed bronze coins in common use at the time. One nummus was worth 50 drachmae, so a loaf of refined bread would have cost two coins, an amphora of good wine fourteen. With average expenditure at 75 nummi per day, Theophanes’s money-men would have had to carry substantial quantities of heavy coinage about with them.

Some of the expenses relate to special occasions. At Antioch Theophanes buys ‘gourds for the wedding of Pellios’. At Ascalon he not only pays for tickets to the theatre and odeion, but also buys a gilt statue of the emperor (Licinius, presumably) for dedicating in a temple, while at Ptolemais he commemorates his daughter’s birthday – probably with another temple dedication. Interestingly, bearing in mind the date, there is no mention of Christianity in these documents; Theophanes’s religious world is still resolutely traditional. The snow-chilled water (chiones hudor) he pays for at Byblos was perhaps a luxury in the summer heat, while it’s tempting to imagine that the ‘wine jar in the form of (the god) Silenus’ that he buys at Tyre was the 4th-century equivalent of a trashy tourist souvenir!

We don’t know whether Theophanes’s trip was successful or not. He spent over two months in Antioch before making his way home to Egypt. Whatever he was doing has left no other trace in the historical record, and compared to the momentous events shortly to convulse the Roman world – the climax of the ongoing civil wars between Licinius and Constantine – his journey may seem of little importance. But these documents give us a narrow window into the everyday experiences of the era, and the lives of those multitudes who lived through a period of profound change, albeit distracted by their own affairs. And for a novelist trying to reconstruct the world of the early 4th century in fiction, they are an invaluable resource.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

John Matthews. The Journey of Theophanes: Travel, Business and Daily Life in the Roman East. Yale University Press, 2006